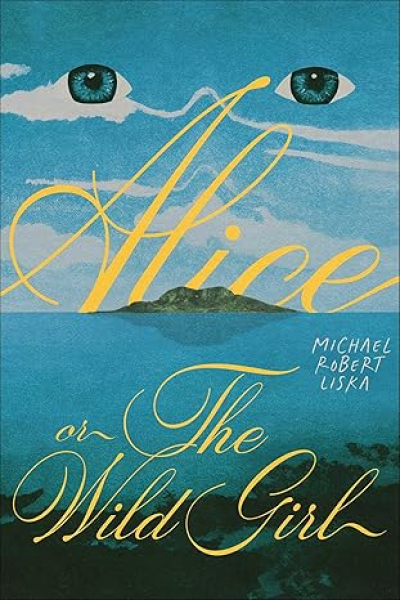

Alice, or The Wild Girl

Alice sat in the darkness of the cabin, waiting for the door to open. On the island she had not been waiting for anything. She’d walked where she pleased, over sandy shore and through the forest, wandering like an aimless ghost among the trees. She listened to the whistling of birds and spent her days sitting on the shore to regard the unending entertainment of waves that crashed and receded. The cabin possessed few such entertainments. She had felt along every inch of it, mapped every joint in the boards with her fingers. Her days on the island had been divided by the sun and moon, by the brief rains that visited her, by a thousand small features of wind and tide and cloud. Now she was surrounded at all times by the same heavy darkness, the shuffling of boots above and below, incomprehensible voices, the blowing of whistles, and the scratching of rats. She had tried to count the ship’s bell to mark the passage of time, but it did no good. It rang once, and then some while later it rang twice, and then later still it would ring three times . . . it counted up to eight rings and then began its meaningless pattern all over again.

She searched in her blankets for a small thing she desired, a momentary distraction. Her hands at first found other things she’d saved: a chestnut with a point on its tip, a chipped coin, a coat button . . . and then she had it: a small, empty tin. She felt the raised impression on the lid, recalling the image she had seen there before. It showed a woman in a long gown, standing on a shore, holding a lamp aloft—she could feel the shape of the woman’s body, the curving line of her golden hair. She traced her finger along the woman’s contours; her awareness traveled down her arm, though her fingers, until it seemed to leave her completely, and then for a brief merciful time she forgot herself and became that woman, holding her lamp to shine light upon the waters.

The sound of footsteps in the corridor called her back. The piglet, which had been quietly sleeping next to her, at once rose and began to pace. She heard the bolt being lifted from its catch on the other side of the door, which opened to reveal the disappointing figure of the boy. He entered her cabin without a word, carrying a plate in one hand and a small stub of candle in the other, melted into the mouth of a bottle. A whisk was tucked beneath his arm. He placed the plate and candle on the floor and used the whisk to tidy the floor. The piglet cautiously sniffed its way towards the plate and began to lap at the food with little sucking noises. The boy took no notice. He was gazing at her.

“Girl . . .” he whispered. “Girl, you girl . . .”

She remained still; it felt as if she could not move when his eyes were upon her. She waited for him to withdraw his gaze. Finally he did, but only to peer into the corridor and softly pull the door closed.

“I wish to tell you something,” he said in a soft whisper. He crouched before her and took her hand into his own. “Can you hear me? I wish to tell you I have grown sweet on you.”

His hand was hot and his smell like soured vinegar. She gave him no answer.

He stood over her for a long while, breathing heavily and saying nothing else. Then he began to fish in his trousers.

“It is only fair that I show you mine,” he said, “because I have seen your titties.”

He came out with his prick in his hand. It was a hairless and blind and pink thing, like a worm or a baby mouse. She thought it looked funny; she had never seen a prick before, and now that she had she wondered at how small and harmless it was. Just a little mouse that hid in a man’s pants. He put it away almost at once, then crouched and put a hand on her shoulder to say, “There. Now we are even.” He tried to look into her eyes but she evaded him. “Do you fancy me?” he asked her.

The sound of more footsteps from without caused him to take up his whisk and his candle. A small bubble of anticipation in her chest, swelling with each footfall. But the door opened again to reveal only the old man, Bird, who stooped to peer within the cabin. Another disappointment. He never entered, only stood stooped like this, his head bent under the door’s low frame so that he looked like some monstrous old stork, smelling of tobacco and bootblack and whiskey.

“Victor?”

“Just finished, sir.”

“Very good, boy. Remember that tidiness of one’s environment leads to tidiness of the mind.”

Bird moved aside to allow the boy to pass into the corridor with his burdens. Then he removed a vial from his pocket and she rose to receive it. The taste of the medicine was bitter on her tongue, but it helped for her sickness, she knew this to be true. When she had it, she felt as if some inner tide had receded, to reveal all of the shells and precious things that had been covered by the waves.

The old man said that it was Easter Sunday, and she tried to recall what these words meant. She could conjure only an image of a roast goose. She could remember the shape of the goose, and that its crisped form had terrified her, because she’d been able to recognize it as a thing that had once flown and honked and she realized that it would never honk again. The edges of its wings had been charred to black. She asked him, “Where have the feathers gone?”

Bird had been saying something, and he paused.

“What was that?”

“The feathers of the goose . . .” she said quietly.

Bird tsked. “This is exactly the kind of behavior I am talking about. You will stop this at once.”

She searched inside herself for a response, but found nothing. At one time, she had been full of words—she could dimly recall as a child when she would babble to her father or mother about the things she had seen, or ask them endless questions about the world. But that had been so long ago. She had not spoken in so long a time that she had lost the habit of it, and words felt useless and unnecessary. She could not find the right ones, and even when she did they would dissipate in the air and lose their meanings as soon as they were spoken.

“Ah,” Bird said, stooping to pick up the plate that the piglet had emptied. “I see you have finished your breakfast.”

Soon after, Bird took his leave and two other men came to guide her through the corridors of the ship. She floated between them; the action of her feet seemed impossibly distant. She thought she was being taken to Bird’s bright cabin, but then she was led to the foot of another ladder. One of the men picked her up and she hung on to his neck as they ascended, up again and through a hatch that was flooded with light.

The naked sunlight that she hadn’t known . . . for how long? . . . now blinded her. A fresh breeze blew over her skin and she could smell tar warming in the sun. She looked down to see that her feet were no longer on the boards. She was being carried along by the men, each with a hand under her armpit. She felt a chair rise up beneath her. The quiet commotion of men in blue coats, arranging themselves in chairs around her.

As her eyes became accustomed to the light she looked up to see again the blue of the sea, the blue of the sky. She was looking out over the entire length of the ship and all along it she could see men, more men than she had ever seen before in one place, all of them crowded upon the deck or hanging in the rigging, lined up on the yards and tops like crows perched on branches, their legs dangling beneath them. Young and old, fair and dark-skinned . . . it was a delegation in which all of the forms that men took in the world seemed to be represented. She saw Lieutenant Bird near the mast. Above him the sails flapped as he spoke more words . . . he was always speaking . . . but even though he shouted the words through a trumpet they were lost to the wind. It did not matter. None of the assembled sailors were watching him. Every pair of eyes across the entire deck was directed at her. This seemed fitting; for her husband William had promised her that one day she would be a queen and men would come to worship her, and that when she died she would be carried to Heaven by a flight of angels. And she was given another thought that caused her to flicker with joy: that all of these men had been gathered there for her. That they ate and moved and breathed upon this ship only to be her witness. And surrounding them all, the familiar endlessness of the sea.

And that is the true meaning of Hospitality, Bird declared through his trumpet. The officers seated around her seemed to stumble into a polite applause that quickly tapered back to nothing.

And then men were rising around her, shifting positions. From her chair, she was the still form that they seemed to revolve around. A figure approached her, bathed in bright sunlight. It resolved into the form of Mr. Rand, with his uniform neatly buttoned, his hair wet against his scalp as if he’d just doused and smoothed it with a hand. Her joy bloomed and filled her up—here at last was the one she’d been waiting for.

“Alice,” he said as he smiled, the sound of her own name still so unfamiliar to her. He bent to whisper a message only for her ears: “Do you know that today is the day that the Lord has risen?”

And she did, she truly did. But there were no words she could find which could possibly express this.

Excertpted from Alice, or The Wild Girl. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Skyhorse Publishing.

Michael Robert Liska is a fiction writer and co-host of the lowbrow Shakespeare podcast What Ho...A Rat!! His work has appeared on Hobart and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, as well as in Epoch, The End, and Forever Magazine. His story “The Child Star” appeared in Heresy Press’ inaugural anthology Nothing Sacred: Outspoken Voices in Contemporary Fiction.