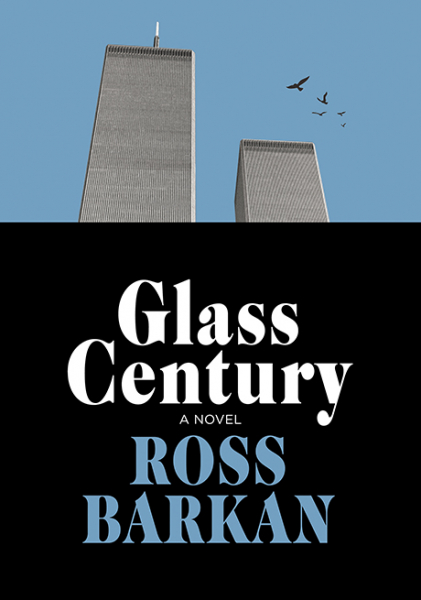

Glass Century

From the BQE she caught the holy hell of it, the way smoke was streaming from burning steel. It was cinema, bad fiction, a plot point dreamed up as too ridiculous for art and discarded somewhere else. She drove on thinking that soon this would all dissolve and she’d be back home, in bed, maybe with Saul at her side. Emmanuel sleeping in the next room, under his Yankee posters. Her phone would ring and it would be Liv. Remember that time—

The radio was beginning to use the word terrorism. It was a distant concept to her, men in foreign lands with submachine guns and hidden bombs, an explosion in a European square. The anchor didn’t seem to be reading the news. He was talking extemporaneously, hunting for adequate adjectives. No one had information. A plane hit the towers, a plane hit the towers. Smoke in the sky, fire, police on the way, state of emergency. The more she heard the phraseology, the less it meant. The machinery of the automobile was an extension of her body, bearing her to her son. Once she was there, she would think again.

Bridge Prep had a clock tower that could be seen on the approach and when it pierced the horizon line, she began to breathe deeply. She was surprised no bombs had landed on the roadway to kill her. What she was increasingly certain of was that the Twin Towers were only the beginning, stage one of a cataclysm, like the assassination of an archduke. War was here. She never kept a gun in her apartment and she wished she had. Saul would be getting out of his appointment soon, which was in downtown Brooklyn.

When would the shooting start? If the bombs didn’t fall immediately, they’d be parachuting out of the sky. Men in black marching downwind, guns pointing straight ahead. She always knew she’d have to run. It was why, more often than not, she wore sneakers. The better to escape crowds, the deadly conglomeration of bodies, death in the crushing heat. The sky was still blue when she parked in Bridge Prep’s visitor lot and sprinted into the building.

It wasn’t as if she would just find Emmanuel, that he’d present himself to her. The school was more a complex, a collection of wings and donor-funded extravagances, a theater and a fitness center and an Olympic-sized swimming pool and glass-boxed computer labs. Though her son had been going to the school for two years now she hardly knew her way around, hoping this carpeted hallway would take her where she needed to be.

When she saw a woman in the hallway who looked like she may know where students were, she stopped her.

“Excuse me, I’m looking for a student, a seventh grader, Emmanuel Plotz. I’m his mother—”

“Oh you should really check at the front desk.”

“The front desk, okay.”

“I’d wait until after chapel. All the students are there now. The headmaster is talking about the situation with the planes hitting the Twin Towers. It sounds very bad.”

Before the woman was done, Mona was running faster than she had in twenty-five years, knocking through the double-doors that split up the long hallway. She knew where they had chapel. It was in the expansive theater, renovated just a few years ago thanks to the donation of a Tony Award-winning producer who had attended Bridge Prep in the ’50s. Up a flight of stairs, a right, then a left, out past the balcony and the indoor swimming pool, chlorine gumming up her nostrils. Another right, a wobbling stairwell, then daylight, a procession of large windows looking out onto a flourishing garden, rosebushes and azaleas. Beyond the garden was the outdoor pool, where Emmanuel had taken summer camp swim lessons when he was younger.

To her left, closed double-doors. Catching her breath, she yanked them open and rushed into the air-conditioned darkness. Hundreds of students were sitting in the theater as the head of the middle school was addressing them about the attacks.

“An airplane flew into the Eiffel Tower—I mean, the Twin Towers, it appears . . .”

Small laughter in the theater.

“. . . we don’t know much yet but we are arranging for a half-day, for school to let out at noon today.”

A boy pointed straight at her.

“Hey Emmanuel, happy birthday! It’s your mom.”

She recognized the boy from Bridge Prep’s summer camp, where she had sent Emmanuel when he was younger. What she couldn’t see yet was her own son. She walked closer, a lone adult proceeding toward the aisles, theoretically unauthorized.

“Mom!”

Usually, she embarrassed him. Children wanted to exist independent of their parents, propagating a fiction that they were living, even at age eleven, self-sustaining lives. It had never been a conflict for her because her parents so rarely ventured out to her place of play. They saw her for breakfast and for supper and that was it. Her mother wasn’t coming to watch her at the schoolyard. Her father was always working. Like other children of the ’50s, she had internalized that whatever it was that her parents didn’t do for her, she would do for her own children, that she would become his world as much as he was already her world. This time, Emmanuel sprung out of his seat and ran toward her, stopping just short of running into her arms. The head of the middle school, still speaking, hadn’t seen her.

“Let’s go home,” she said.

At the front desk, she told security to communicate to the school that Emmanuel Plotz was leaving for the day. “I’m his mother,” she said with finality, pressing his hand tight. In the car he didn’t speak, staring straight ahead. They drove the short stretch home, the radio shut off.

“Mom, what exactly happened?”

“We don’t know yet. The planes hit both towers. It could be an accident. They’re still getting information.”

“Were you down there?”

“I was.”

She decided, against instinct, to turn on the TV when they were inside. Every news station showed a continuous shot of the burning towers, the angles varying only slightly, eyewitnesses calling in from cellphones to explain to the broadcasters what it looked like to watch two of the tallest buildings in the world burn. The eyewitnesses were interchangeable to her, their phones crackling, their voices fluty and distant, their stories hinging on the unexpected absurdity of a plane flying directly into an office building. When she had poured Emmanuel a glass of water, she walked into her bedroom and called Saul. She couldn’t think of what else to do.

The call went straight to voicemail.

Saul wasn’t up there. That she knew. Yet he could have been and that made her deeply, suddenly sick, like the planet beneath her had been wrenched at a radical degree previously unknown in human history. She was teetering, her knees weak.

She called Liv.

On the fourth ring, she heard a voice.

“Mona, hey.”

“Liv, how are you, are you down?”

“We’re—there’s a lot of smoke. It’s very hot here. We’re trying to get, to get to a place where there isn’t smoke. Grayson—”

“Where the fuck are the firefighters?”

“I don’t know.”

“God, I’m going to call the fire department.”

“I’m sure they’re on their way.”

The phone cut off. She called again and Liv’s voicemail came on. Hi, this is Liv, please leave a message and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can. Thanks! She dialed a second time. Hi, this is Liv, please leave a message and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can. Thanks! She dialed a third time. Hi, this is Liv, please leave a message and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can. Thanks!

She slammed the phone down and sat down hard on her bed. Her eyes felt very hot.

“They’re saying a plane hit the Pentagon,” Emmanuel said quietly, pointing at the TV.

“The Pentagon?”

“Yeah.”

They sat together on the couch, her arm around his shoulder. There was a split screen of the black smoke pouring from the Twin Towers and the fire at the Pentagon. She had no idea if this was what they should be doing now. All they were going to do was watch the same images of the buildings burning ad infinitum until someone figured out how to put the fires out. Helicopters would have to make rescues. She imagined one, a sturdy FDNY chopper, freeing Liv and Grayson from their smoke-clogged prison.

A broadcaster said the President had made a statement. Terrorism against this nation will not stand. We will hunt down those responsible.

Now there was a shot of another broadcaster outdoors, standing on top of a building somewhere north of the Twin Towers. Just over half his face was in shadow. Then there was a cutaway back to the Pentagon.

As a broadcaster explained the confusion at the Pentagon, the first broadcaster called out from off camera.

“Wow, I need you to stop, I need you to stop for a second. There has just been a huge explosion and you can see a billowing smoke rising and I can’t—I can’t see that second tower but there was a cascade of sparks and fire and it looks like, wow, it looks like a mushroom cloud explosion, this huge billowing smoke in this second tower, this was the second tower hit, and I cannot see behind that smoke. The first tower in front has not changed and we see this extraordinary and frightening scene of this second tower just encased in smoke. What’s behind it I cannot tell you. That is about as frightening a scene as you will ever see.”

She was gripping Emmanuel’s hand. He was holding his glass of water, not drinking.

“He’s an idiot,” she said softly.

“What mom?”

“The building isn’t encased in smoke. It’s gone.”

She couldn’t cry because if she did, Emmanuel would. He would see her and sob. When she was twelve, ready to turn thirteen, Cuban missiles almost killed them all. But they never came. This was the unsaid assumption of American life in the twentieth century. Apocalypse could approach, threaten, menace. It could suck the lifeblood out of imaginations. What it could not do was arrive. This is what made the genre of fiction so tolerable, why someone like Al could tell her about a comic book in which a false alien attack kills three million New Yorkers to save the world and she could nod along, safely perplexed. This was not supposed to be the counter-world. Airplanes did not topple buildings.

The TV showed the tower collapsing again. It was the South Tower, the broadcaster said. This meant the North Tower was standing. Liv was there. She could get downstairs and get out.

“Emmanuel, honey, give me a second. I have to make a phone call.”

Hi, this is Liv, please leave a message and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can. Thanks!

She fought the sensation that she was listening to a ghost. Liv couldn’t talk because the firefighters had her and they were racing down the stairs, dousing flames with their high-pressure nozzles. Or the helicopters had arrived. CNN wasn’t saying anything about helicopter rescues yet.

The cloud, taller than the buildings around it, was filling downtown.

“Why is this happening?”

“I’m not sure. We’re still figuring it out.”

“Why did they do it?”

His hazel eyes were wide, lightly bathed in the soft glow of the TV screen. He seemed beyond tears, in a state of shock and reckoning she couldn’t quite describe. She didn’t know why they were watching anymore. There was no purpose to this kind of observation. They were adding nothing, saving no one, offering merely their fear. They were two useless specks of an equally useless mass audience. For the span of her adult life, she had told herself that through actions taken or refused, she could alter the trajectory of her reality. She could hustle after the ball, smash the serve harder, make a new demand of her body—it was all possible, if only she tried hard enough. In a way, it was the most American thing about her. It was, she had come to understand, her private manifest destiny.

She felt weaker the more they watched. Time was like the crawl of blood from a flesh wound, a bright streak rolling to the ground. The broadcaster was outside again, on his midtown building, his face in shadow. He continued to describe the smoke and the fire as if he were delivering new revelations, his necktie crisp and power red. Every few seconds, he reused an adjective. Extraordinary. Terrifying. Unprecedented. He was advertising the uselessness of human language.

She buried her face in her hands and hoped somehow Emmanuel wouldn’t notice. What she wouldn’t do was cry, not one tear, not now. Later tonight, under the covers. New York City would have a single ruined tower, a monument to the most fucked up single day in anyone’s lifetime. She imagined visiting it with Liv, the smoldering memorial, Windows on the World blackened in the sky. Liv would need to find a new job. An episode of Seinfeld briefly came to her, George struggling at the unemployment office.

“Mom.”

In Seinfeld, the Twin Towers don’t fall to the ground.

“Mom.”

“I see it, Emmanuel.”

“Both of them.”

The second tower, like the first, collapsed into a colossal cloud of fire and dust. The broadcaster was no longer trying to understand what was happening. Instead, more adjectives: remarkable, catastrophic, horrifying. A coordinated act of terrorism. Mona reached over and turned the TV off.

“Let’s not watch this anymore.”

An indeterminate time later, her landline rang. She answered it without checking to see the number.

“Mona, are you okay?”

“Yes. I’m home with Emmanuel. How are you? Are you still at the dentist?”

“Feeling sore and like shit but the least of my problems. I’m heading your way now.”

“When I saw the second plane hit, I fled.”

“Thank God you got out. They’re saying lower Manhattan is just covered in dust clouds. It’s unbelievable. All of it. I thought I had seen it all, genuinely. JFK assassinated. King assassinated. I remember the end of World War II. Sixty years, and I thought I had seen enough.”

“I don’t know what this is.”

“Terrorism is the only word. Every three seconds, on the radio. I’m trying to see what intel I can get. It probably won’t be much. No one knows anything.”

“It’s a war, then.”

“A war, yes. If this isn’t a war, a war will come out of this. I’m near the exit now. I’ll be there in a few minutes.”

“Stay on the phone until you’re here, Saul. Please.”

“Okay, I will. How is Emmanuel doing?”

“He’s shocked. I turned the TV off. We’re just here. I’m figuring out what I should do, if I should bring him to a friend’s house or keep him here.”

“It might be better if he’s with other people too. I don’t know. I’ll be there soon, though. We’ll figure this out together.”

He came into the apartment in his shirtsleeves and tie. They hugged tightly and he kissed her. Emmanuel came running to him, hugging him. In the corner of the living room, the TV was a dark mirror, their merging forms bent in the glass.

“Are the Yankees going to get to play tonight?” Emmanuel asked him. “I really want to watch.”

“I think they may cancel baseball until they figure out what exactly happened.”

“We saw what happened.”

“I mean who did it. It’s going to be a very confusing and scary time, Emmanuel, but your mom and I are here for you, okay? We’re right here. We aren’t going anywhere.”

They went outside together for a walk. Holding hands, they moved gingerly, dazed in the sunlight. She felt like a mannequin come to life, her legs uncharacteristically stiff, Emmanuel shuffling between them. They walked down the long stone steps to the highway overpass, which would take them to the waterfront promenade. By now, Liv would have gotten out. There were people who ran down the stairs before the Towers fell. She would run ahead of Grayson, the older man huffing, smoke choking but failing to kill him. They would emerge covered in ash or just tired and pale, elegant still, marching out into a brigade of firefighters and police dispatched from the outer boroughs to save their lives. At some point, Liv would call. Her cellphone was likely dead. Before getting home, she would have to stop in to the hospital. Doctors would check her vitals, ask about smoke inhalation, feed her and dress wounds. The process could take all day.

A titanic funnel of smoke trailed above them. It had come impossibly far, from the crater in Manhattan. When Mona saw the smoke, free now from her television screen and dominating Brooklyn sky, she could understand that this was not merely a historic day. It would be a day that triggered a new timeline entirely, a divergence that would haunt them all until they died. She was living and breathing through a pivot point. Kennedy’s death had been one. Then, she had been a befuddled ninth grader, looking on as her social studies teacher sobbed into a napkin. A man, though—even an American president—was not one of the tallest structures in the world. His death did not mean thousands of others could be dead too.

“My office is definitely gone,” Saul said flatly as they stood together on the promenade, one group of many who had come, absent any ideas, to stare at the cloud over Manhattan.

“It’s possible it stood up in the wreckage.”

“No.”

“I should call Liv again.”

“Yes. Give her a ring. I’m sure she’s with Grayson.”

Mona listened to the voicemail again. Was it possible Saul believed with the utmost certainty that his office had been annihilated and Liv and Grayson were alive? Could both ideas be held together? She was seized with the notion that Saul’s office must be preserved for the two of them to be living and if the collapsing towers had flattened Saul’s new World Trade Center perch then it was possible she would have to confront a probability she was not yet ready for, that seemed less tragic than beyond the realm of belief altogether—Liv not being alive. She was running one of the most famous restaurants in the fucking world. She was dating one of New York’s most eligible bachelors. Saul was going to meet him for a job at the Port Authority. The meeting was still on. They just couldn’t do it at the Trade Center.

“Where do you think your meeting with Grayson will be? If you each don’t have your offices?”

“You know, I have no idea. They’ll probably set up a temporary office somewhere. I just don’t know where. All of this is bewildering.”

“I don’t think we’ll have school tomorrow,” Emmanuel said quietly.

“You can stay home no matter what,” Mona said.

Just a few hours ago, she was getting ready to photograph a primary. Saul was having a tooth pulled. Emmanuel was in school, another Tuesday. When did another Tuesday become the Tuesday? When was history wrenched? Who dared to insert themselves into the course of events? Who could? She was still waiting for the second wave. Military planes traced the sky. She was looking for bombs, the death from above. There was nowhere to be safe. Not out here, among the crowds leaning over the promenade railing, their necks outstretched toward the great cloud of smoke.

“Has the News been bothering you?” Saul asked.

“No. And if they do, I’ll them to go fuck themselves. Particularly my desk editor.”

“Yeah. Don’t go back into the city. Not now. It doesn’t look good.”

“This still feels like a dream.”

“I remember reading something about the samurai, how they said life was the dream and death its awakening. I almost understood. Today is one of those days where you see the logic.”

“I don’t feel awake. I don’t at all.”

Emmanuel, they saw, had begun to cry. He was nearly silent, straining to suck tears back into his body. He appeared smaller, curled inward, his head pitched toward the ground. He was hoping they wouldn’t see him.

She put her arm around him, not saying anything. Saul rubbed his back. Until now, the words would always find their way to her, language unfurled when it needed to be and put to use in calming him. She believed in the brightness of the future. She believed she could protect him. This belief informed every interaction, every pep talk, the readings of history before bed. Through bloodshed, progress was always perceptible. The Nazis were defeated. The Civil Rights movement overcame Jim Crow. Women’s liberation beat back sexism. At the end of the day, a lesson.

What struck her was how absent of lessons this day was. There was a crater of smoke and fire and death, unknown bodies charred and crushed.

She told Emmanuel it was okay to cry.

Excerpted from Glass Century. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Tough Poets Press.

Ross Barkan's latest novel is Glass Century. He is a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for New York Magazine. His work has appeared in a wide variety of publications and he maintains the popular Substack newsletter Political Currents. In 2025, he co-founded The Metropolitan Review, a book review and culture magazine.